Spring 2018

Instructors: Andrew Kudless & Nathan Lynch

with CCA Digital Craft Lab & CCA Ceramics

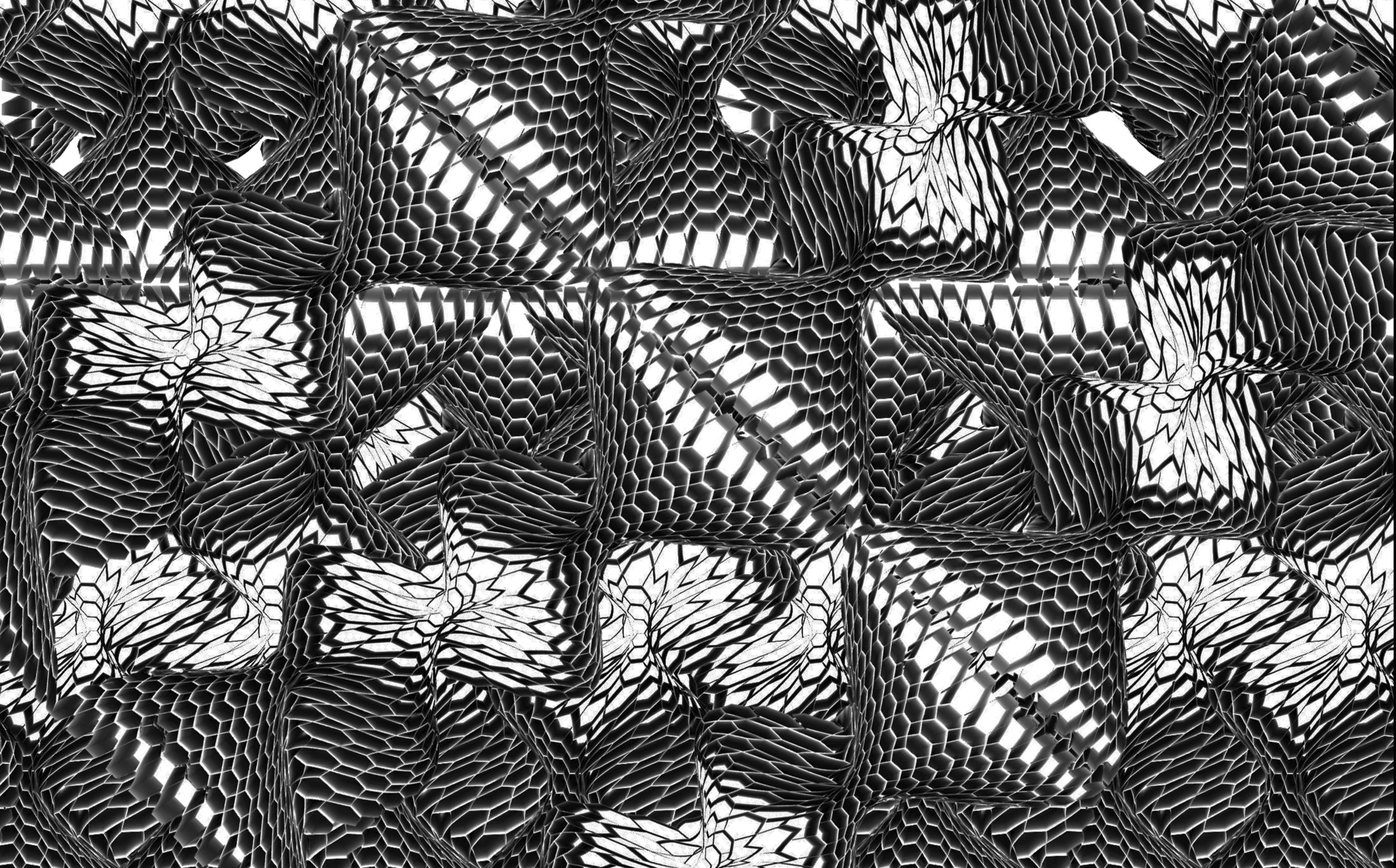

The various creation myths of architecture often alternate between early man either occupying found forms such as caves or constructing a primitive hut. Vitruvius mentions both of these possible origins for Architecture but he also mentions a third which is often forgotten: maybe humans first started building by watching more advanced builders: animals. Although we often think of architecture as a human activity, the diversity and sophistication of animal architectures are astounding. From wasp’s nests to beaver dams, animals have developed highly complex domestic spaces that often surpass the material, environmental, and structural performances of human-built forms. These nonhuman architects use a variety of materials such as straw and wood, however, many use earthen materials such as soil, mud, and clay to, in their own unique way, 3D-print their homes.

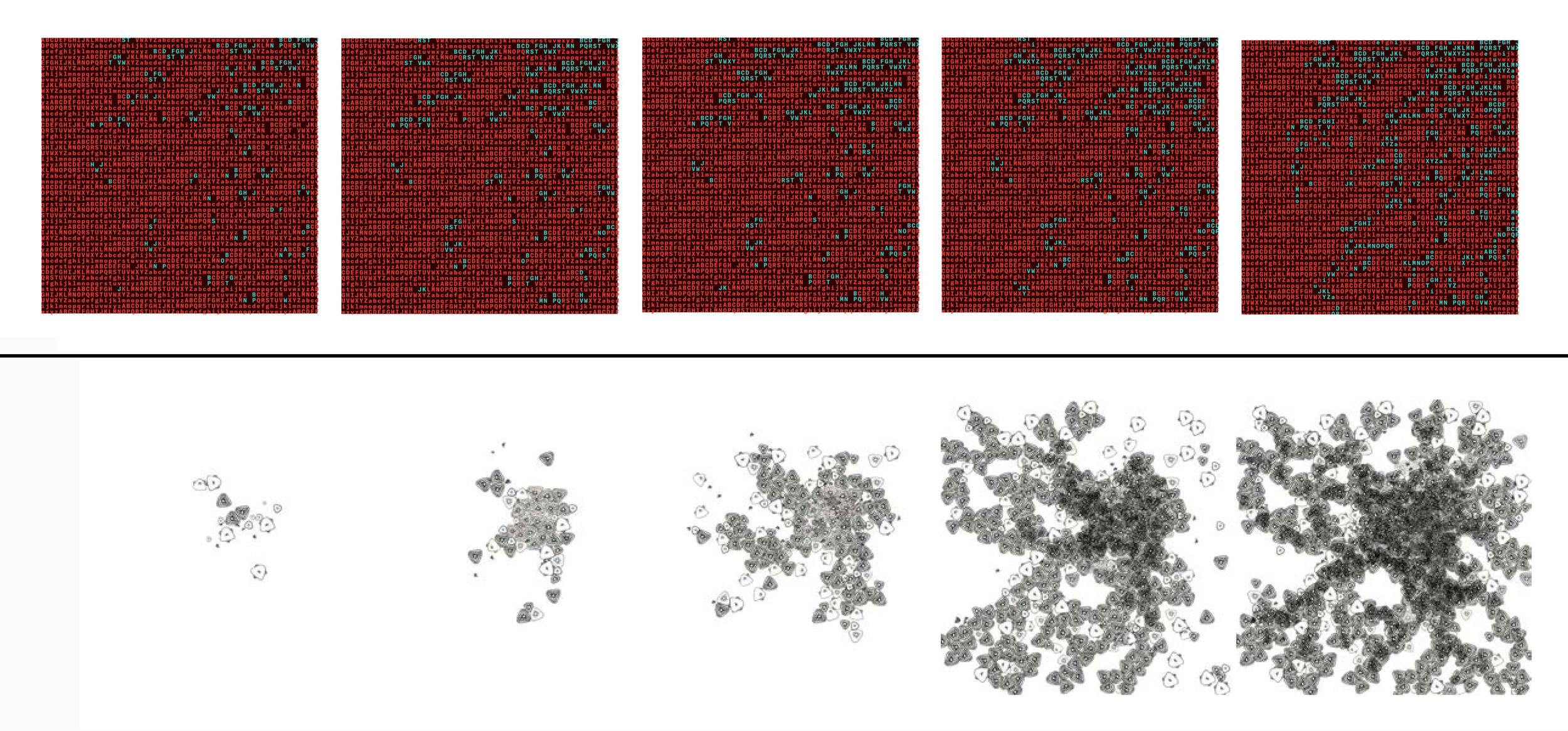

We will use this alternative history of architecture as a starting point and source of inspiration on how we, as human architects, might conceive a different way of designing, building, and occupying domestic forms. The studio will focus on the act of extruding earthen materials as the primary building technique and develop modular and parametric bricks as the primary building system. This combination of primitive material with advanced technology serves as one of the primary research areas of the studio. Although we will start with basic clay and simple toolpaths, students will be encouraged to experiment with new recipes and more complex toolpaths as the term progresses in order to produce new building performances.

In addition to creating domestic space for humans, the studio will also explore how human-built structures could support the dwelling of nonhuman species, particularly those undergoing habitat loss. The human act of building for animals has a long architectural history primarily centered on transactional exchanges between species. From bee apiaries and dovecotes to silkworm cocooneries and dairy barns, humans have been creating structures for nonhumans for centuries in order to benefit from these creatures: foods such as honey, eggs, and milk but also raw materials such as silk and even less tangible exchanges such as heat and companionship. However, urbanization and industrialization have increased the physical and conceptual distances between humans and nonhumans. Furthermore, the way in which contemporary architecture engages the nonhuman world could generally be categorized into total rejection (pests), reduction (sustainability’s focus on energy), or benevolent separation (the picturesque). The studio will look beyond these and attempt to discover (or rediscover) other ways of living with the nonhuman.

In an age when we are finally recognizing the extent of our deep relationships with the environment around us and the microbiome within us, the studio will seek a form of solidarity with the nonhuman. We will research how domestic architecture might serve as the medium to reevaluate the politics, cultures, and ecologies of living near and with other species. Students are encouraged to develop radical approaches to the siting, programming, and ecologies of their domestic designs in relation to both human and nonhuman clients.